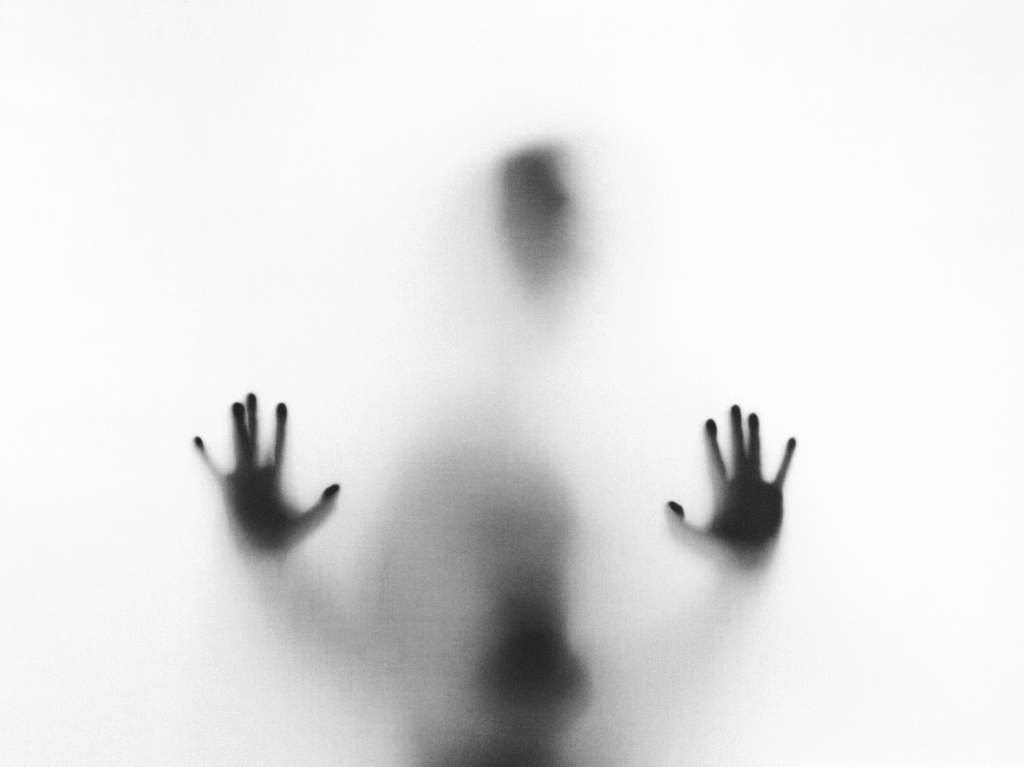

When the monster knows your name

by Renato Gandia

I

The night in Maragondon, Cavite smelled of damp earth and smoke residues from a pile of dried mango leaves my uncle was burning earlier, the air thick enough to drink. I was ten years old, sitting on the bamboo floor of my paternal grandmother’s house, knees drawn to my chest, listening to the hum of the kerosene lamp because there was another power outage. Outside, the mango trees shivered in the wind, their shadows stretching like fingers across the yard.

Nanay Ding, my grandmother, had just finished telling me to close the windows before nightfall. “Para hindi makapasok ang aswang,” she said, her voice low, as if the creature might be listening from the dark. Her words lodged in my chest. The aswang—that shapeshifter whispered about in every barrio, part woman, part predator—could be anyone: the market vendor with the friendly smile, the neighbour who offered sweet suman, even the quiet aunt who kept to herself.

The grown-ups never said it outright, but I could feel the edges of their fear. They talked about the tik-tik, the birdlike sound the aswang made as it drew near, how it was loudest when the creature was still far away, and quiet when it was right outside your window. That night, I strained to hear it between the chirping of crickets and the occasional bark of a dog.

From the far side of the house came the clink of dishes and the muffled laughter of my aunts. The thin walls made every sound close, but beyond them lay the vast dark of Maragondon’s fields, where the river slid past banana groves and the earth smelled of water and secrets. I thought of the aswang moving through that dark—silent, patient, wearing the face of someone I might greet in daylight.

I didn’t know it then, but I would meet many more aswangs in my life. Not the ones with wings or dripping fangs, but the kind that move unseen through offices, through politics, through the glowing blue light of a computer screen. The kind that wears respectability like a mask, smiling as they drain the lifeblood of communities, of trust, of hope.

II

The aswang has been with us for centuries, older than the towns and barrios whose stories keep it alive. In some places, it flies on leathery wings, hunting for the unborn. In others, it walks on human legs by day, speaking softly, passing as an ordinary neighbour until nightfall. In certain regions, it can split its body in two, leaving the lower half hidden while the upper half glides through the air in search of prey.

It has never been just one creature. It shifts—woman to bird, dog to man—slipping between forms as easily as it crosses the threshold between the familiar and the terrifying. Sometimes it is a vampire, sometimes a ghoul, sometimes a witch, and sometimes all three. Its danger lies in its ability to blend into the everyday until it chooses to reveal itself.

In the oldest stories, the aswang was not merely a nuisance or a shadow at the edge of the yard. It was a force of concentrated harm, as relentless as hunger itself. It could slip into a house without disturbing the air, its long, hollow tongue sliding through the smallest crack in the walls to draw the breath or blood from a sleeping victim. It was said to uncoil intestines like ribbons, to leave a body emptied but whole, as if death had crept in on its own.

No prayer could drive it away once it had chosen you. It moved with the certainty of nightfall, feeding on what was most precious—the unborn child, the freshest corpse, the vitality of the strong—because to take those was to unravel a family’s future. People feared the aswang not just for the deaths it caused, but for the way it warped the living left behind, filling them with suspicion and grief.

It was a predator of more than flesh. It was a breaker of bonds, a sower of mistrust, a reminder that safety was never certain, even among kin. This was the true terror: that it could make a village doubt itself until the silence between neighbors grew wider than the fields.

In the old rural tales, the aswang was a warning: pregnant women told not to go out at night, children told to stay close to home, strangers eyed with suspicion. These stories kept invisible boundaries in place, shaping behaviour through fear. Yet the aswang also thrived on uncertainty. It lingered in silences, in rumours, in the unexplained death of livestock or a sudden wasting sickness no one could name.

What kept it alive was not proof, but possibility.

III

The aswang of my childhood lived in the dark edges of the barrio, but the ones I know now do not need the cover of night. They thrive in broad daylight, often dressed in pressed suits or lit by the glow of a phone screen. Like their folkloric counterpart, they shift shape to fit their surroundings, wearing whatever face will earn them trust before they feed.

Some smile from campaign posters, promising reform while quietly draining public coffers. Others sit in corporate boardrooms, extracting not blood but resources—forests stripped bare, rivers poisoned—leaving the land and its people weaker than before.

They haunt social media too, not to steal bodies but to consume attention and sow division. Disinformation spreads like the quiet flutter of tik-tik wings: the closer it gets, the softer it sounds, until you don’t notice its presence at all.

And then there are the ones that live within us—the self-doubt, envy, and shame that shape-shift into something that feeds on our own confidence. They are perhaps the hardest to recognize because they speak in our own voice.

The genius of the aswang is not in its power to kill, but in its power to pass—to move unseen, to adapt, to belong just enough until it no longer needs to pretend. In this way, it remains a perfect metaphor for the forces that threaten us today: invisible until they are inevitable.

IV

The aswang has survived because it is never only one thing. It does not live or die in the way other monsters do. It migrates. It adapts. It slips across geography and time, wearing whatever shape the moment requires.

Once, it flourished in places where medicine was scarce, where darkness came early and the night was thick with sounds the ear could not name. Fear was a kind of survival, and the aswang gave that fear a face.

In the diaspora, it changes again. Among Filipinos in Canada, the aswang can stand for the quiet erosion of identity—the slow forgetting of language, the flattening of accents, the urge to make oneself smaller to fit. It can also be a name for the more systemic forces: the racism that hides behind politeness, the bureaucracy that grinds hope down with paperwork, the pressures that drain without leaving marks.

Its most potent weapon has never been claw or fang, but the gift of passing for human. In every era, it reminds us that the threat is often hiding in plain sight—sometimes across the street, sometimes across a boardroom table, and sometimes in the mirror.

V

I think of that night in Maragondon often—the kerosene lamp’s thin flame, the smell of damp earth, the way the shadows of the mango trees moved like they had a life of their own. I was ten, straining my ears for the faint tik-tik, convinced the danger would announce itself if I only listened hard enough.

What I didn’t know then was that the aswang rarely arrives with warning. It does not always come with wings or claws. Sometimes it comes with a handshake. Sometimes it comes with a smile. Sometimes it comes wearing your own face, whispering that you are not enough.

The world I live in now is far from that bamboo-floored house, yet the aswang has followed me here—through airports and office buildings, through glowing screens and quiet moments of doubt. It still waits in the dark, still shifts its shape, still feeds when it can. But I have learned something my ten-year-old self did not yet understand: naming the aswang is the first act of resistance.

We tell its story not because we believe in monsters, but because we know they believe in us.